Joint (In)Stability in Hypermobile Bodies (Hypermobility Series #1)

Part 1: Active vs Passive Stabilisation

To kick off our journey of understanding joint stability as a person with hypermobility, let’s start with the most basic foundation of the human body: The Skeleton!

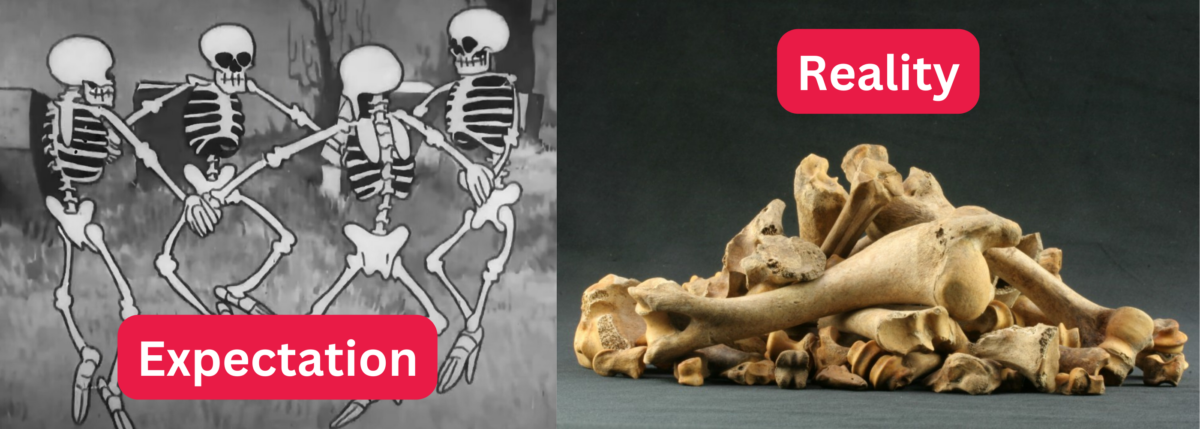

Unlike in old timey cartoons, if we magically stripped away everything in your body and just left the bones, you wouldn’t be able to stay standing, much less dance around a graveyard with your pals. Beyond that, none of your bones would even stay connected to each other. You would just collapse into a shambled pile of loose bones on the floor.

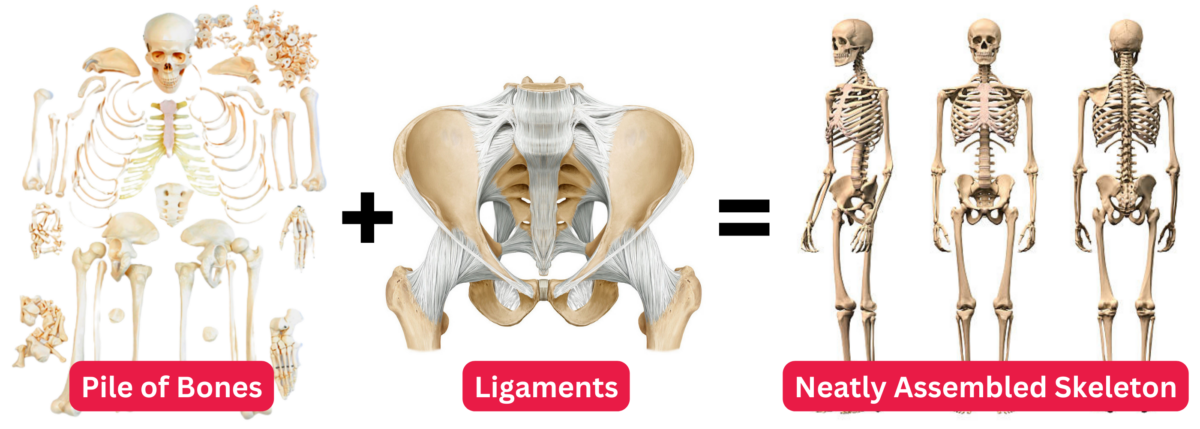

However, if we were to add just a single type of tissues back to your body, we’d have a fully assembled skeleton, instead! These structures we’ve just added back to the body are called ‘Ligaments’.

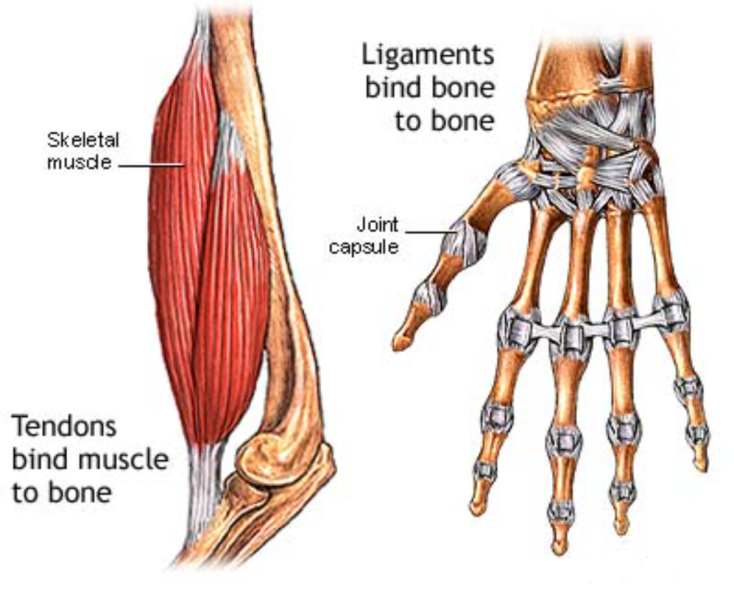

Ligaments are what connect bones to other bones, and are part of a broader category called ‘Connective Tissue’, for hopefully obvious reasons. While there are many types of connective tissues, for the sake of simplicity we are just going to focus on two.

The first, as we have established, are Ligaments. The second are called Tendons. Whereas ligaments connect bones to other bones, Tendons connect muscles to bones. Muscles have the big job of allowing us to produce movement, even acting to overcome gravity and external load, so tendons have a pretty critical job in making that possible.

However, producing movement/acting against gravity is not the ONLY job of a muscle. Ligaments get the lion’s share of the glory for holding us together (in other words, ‘providing stability’), but muscles share this job too! The relative contribution of muscles vs. ligaments, however, in terms of who provides the most stability is different from one joint to the next.

(Side note: The kind of stability that ligaments (and bones, and other tissues we haven’t discussed) provide to a joint is called ‘passive stability’, whereas muscles provide whats called ‘active stability’. I am going to use these terms from now on instead of continuing to refer to ligaments and muscles.)

Some joints have a high degree of passive stability, and so do not need much active stabilisation. (In other words if that doesn’t make sense yet, the ligaments do their job well, so the muscles can be left to just focus on moving us around.)

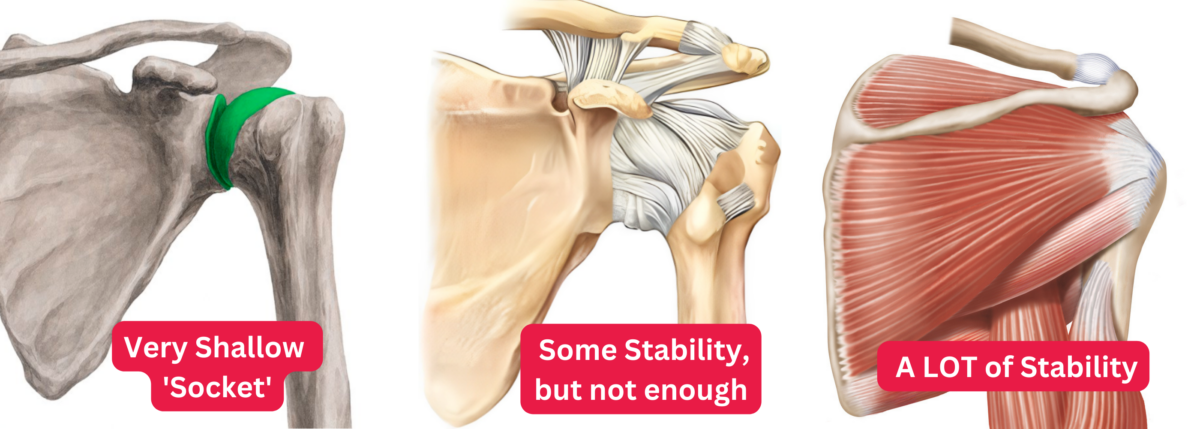

However, this is not the case everywhere. This is best illustrated in the shoulder joint; the one made between our upper arm bone and our shoulder blade. This is a ‘ball and socket’ joint, but the socket is very shallow. Its less of a socket and more of a ‘dinner plate’ shape, as shown below on the far left.

This shape is good for us because it means our shoulders have a huge range of movement compared to our other joints (just think of all the directions you can move your shoulder in, compared to your knee or elbow). However, in order for the joint to maintain that huge range and variety of movement, the ligaments cannot be as snug and tight as they’d otherwise like to be to provide their signature ‘passive stability’.

This relationship is seen more or less everywhere in the body. The higher the passive stability of a joint, the less variety and range of movement that joint generally can have. Conversely, the greater the movement any individual joint has, the less it will rely on passive stability, and the more it will tend to rely on active stability.

Since the shoulder joint is passively less stable, it needs more active stabilisation from the muscles instead!

Take-home Point #1: Ligaments (among other things) provide passive stability, Muscles provide active stability. They team up to hold you together, but sometimes one is more important than the other in different parts of the body.

How Does This Relate to Hypermobility?

Well, with hypermobility, our ligaments do not have the same strength, ‘tightness’ or rigidity as others. They are a bit looser and stretchier, and so do a worse job of holding things snugly together.

This means we have less ‘passive stability’, across our entire bodies. This is also why hypermobility MAY* allow people to move their joints way further than other people. It is also why hypermobile people can regularly experience their joints coming partially (subluxation) or completely (dislocation) out of socket/place.

With less passive stability, as we’ve outlined already, comes a greater reliance on active stability. This means that if you want your joints to feel more stable and experience joint subluxation/dislocation less frequently, you need to have strong muscles. Not just strong muscles, but proportionally strong muscles. That nuance will be what is covered in the next below, in ‘Part 2’

(*This is not true in all cases, and in many, it can be the exact opposite, but this will be explained in a future post)

Part 2: Muscle Tone and Antagonist Balance

So now that we’ve established in Part 1 that folks with hypermobility tend to have less passive stability (from ligaments + other connective tissue), and so we rely far more on active stability (from muscles), this part of the series is going to explain how the way muscles stabilise a joint is a little more complex than the very straightforward way connective tissues do, how this process can ‘go wrong’, resulting in joint pain, subluxation, dislocation, etc., and how we can work to resolve that.

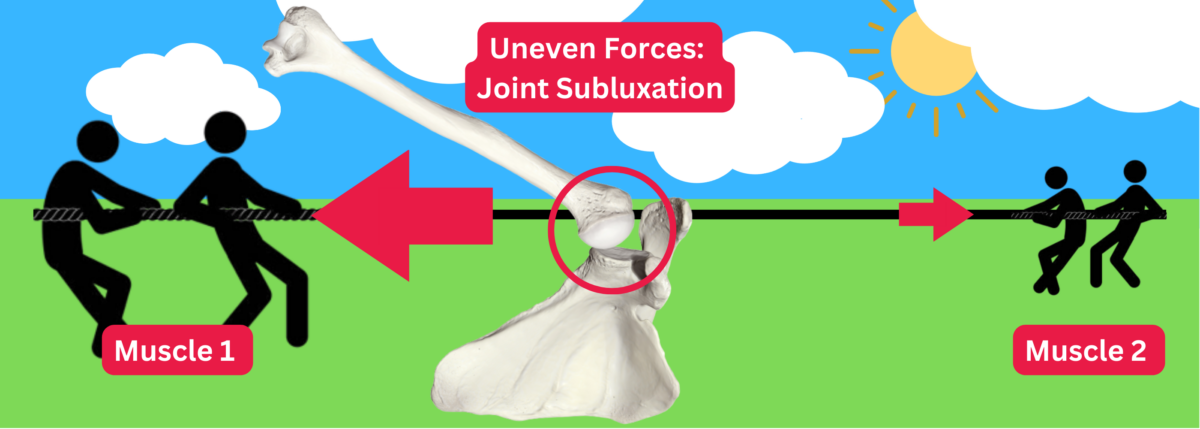

To do this, we are going to imagine a game of Tug-of-War.

(DISCLAIMER: This is an extremely simplified model of how this all works. There is a lot of nuance being stripped away for the sake of ease of understanding, so do not take this as gospel of how everything EXACTLY works.)

For anyone not familiar with the game, these two images (above and below this text) explains it. There are two teams of people pulling on a rope in opposite directions. there is a tag, flag or marker of some kind in the middle of the rope, and two lines on the floor. The goal of the game is to pull harder than the other team to get that flag over the line on your side (bottom photo).

The way muscles stabilise a joint ‘actively’ is very much like a tug-of-war.

Muscle Tone and Antagonist Strength Balance, Very Simplified:

If we go back to this concept that the main job of muscles is to produce movement, it paints a picture that muscles are only ‘turned on’ when you choose to move. E.g. If you are sitting in your chair, the muscles that bend your elbows are ‘turned off’ up until you decide to bend your elbow to scratch your chin, so they ‘turn on’ to achieve that, then ‘turn off’ again when you’re done.

This is not how muscles actually work! In order to complete their second job of active stabilisation, all the muscles in your body have a very low level of constant muscle contraction that they maintain more or less at all times even when its relaxed/not flexed. This is a concept known as resting ‘Tone’.

If we now imagine our tug-of-war again, but instead of people pulling ropes attached to a flag, It’s muscles pulling on tendons attached to your shoulder. Similarly, instead of a space between two lines on the floor, it’s the joint ‘socket’ in your shoulder blade.

The constant force each muscle is exerting on the tendons attached to the joint when you are totally relaxed is its ‘tone’. Importantly, the amount of tension a muscle supplies to a joint through tone depends (among other things) on the strength of that muscle.

To provide a crude numerical example (a lot of made up numbers coming up)

Imagine a muscle in your shoulder that is so strong that it can exert 50 (arbitrary units of) force if it tries its hardest. Let’s call this Muscle 1.

Now imagine Muscle 2, another muscle that for some reason (most likely weakness), can only exert 20 units of force if it tries its hardest.

Now imagine these muscles pull on opposite sides of a joint, and so perform opposite functions. These muscles are then called ‘Antagonists’ of each other. (e.g. in your elbow, the muscle that bends the elbow and the muscle that straightens the elbow are ‘antagonists’ of each other.)

If we imagine that a muscle’s resting ‘tone’ is 10% of its max strength (entirely made up), then that means Muscle 1 can comfortably apply a constant force of 5 on the shoulder at rest. Conversely, Muscle 2 is only able to comfortably apply a force of 2 at rest.

As in a tug-of-war where one team is pulling harder, the flag crosses over the line and they ‘win’ the game. From the joint’s perspective, this is what we’d call subluxation (or if it’s WAY over the line, then dislocation).

The picture painted above is a simplified image of what can be going on in the joints of a hypermobile person who has weak and/or imbalanced muscles, and as a result, has a near constant feeling of ‘wrongness’ in a joint. This joint may even be able to be momentarily ‘clicked’ seemingly back into place, but this relief lasts for a very short time and/or or it requires very little perturbation to go back to its original feeling of instability and possibly (but not always) pain.

All of this should serve to really drive home the point that having not only strong muscles, but balanced and proportionally strong muscles is a significant key to reducing the incidence and/or severity of joint subluxation in a hypermobile body.

Practical Implications

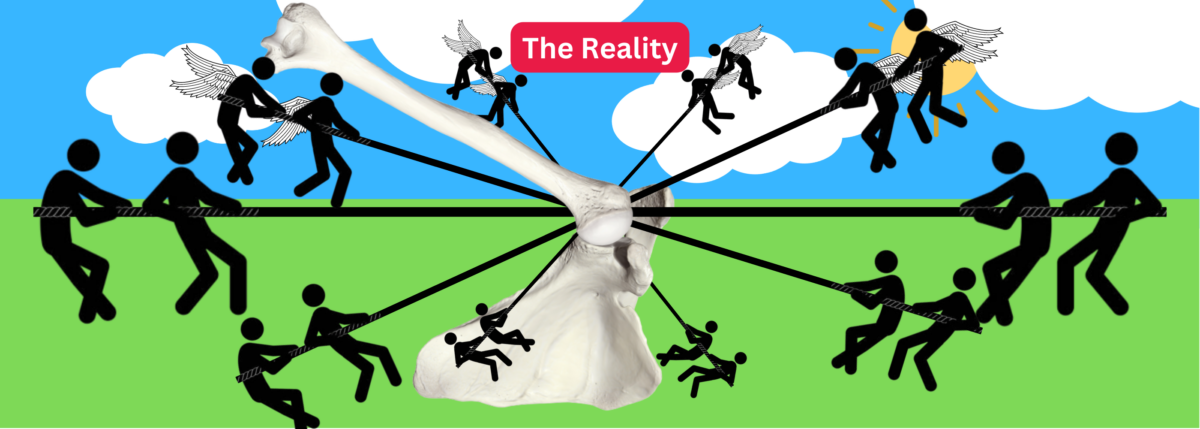

If the body were as simple as the model I just outlined, achieving this would be easy-peasy lemon squeezy. Either muscle 1, or muscle 2 is too weak. Make that stronger, and you’re fixed!

For most joints in the body, however, it is not a single neat tug of war going on. Rather, it is many, many numerous tug-of-wars all happening at the same time in a whole bunch of directions at once.

This quickly turns the process of trying to ascertain whether/which specific individual muscles may be contributing to a joint’s instability into a fool’s errand for anyone other than an expert in musculoskeletal anatomy (like a qualified, hypermobility-educated physiotherapist). Understandably, this can make the process of trying to take management of your symptoms into your own hands seem like a daunting and impossible task.

In an ideal world, every hypermobile person would be able to work with a qualified, knowledgeable professional who is able to specifically assess their body and make them a program based on their individual needs and personal weaknesses, where they are able to address and solve issues that crop up as they go along.

However, the reality is that access to high quality healthcare for hypermobility related problems is currently very few and far between. Those who are able to access healthcare for their issues may yet still be met with healthcare professionals that are not sufficiently educated on joint hypermobility, that advise hypermobile patients to avoid all sports/exercise/physical activity without medical supervision, or sometimes to avoid exercise completely as a ‘better safe than sorry’ approach borne from a lack of understanding of the condition.

Given the critical role that strong muscles have in holding hypermobile bodies together, and the role that inactivity has in causing muscular atrophy and creating weakness, this ‘better safe than sorry’ advice tends to cause more harm than benefit for hypermobile folks in terms of encouraging further instability.

While it is always better to have an expert by your side, and you should always seek that kind of support and guidance if you can, it is still possible to independently begin the process of strengthening your body, and for this process to be safe.

In the absence of the professional expertise required to identify your weak points, independently starting on a workout program that aims to strengthen your whole body proportionally (as opposed to focusing purely on the muscles you can see in the mirror), that is appropriate for your current level of strength and function is the next best bet. This full body strengthening approach acts as a wide net to catch as many of the ‘low hanging fruit’ of muscle weakness as possible, while always making sure to be proportionally strengthening opposing/antagonist muscles.

Where I Come In:

Two examples of such a full-body strengthening program are my BWF Primer and Bodyweight Strength Foundations routines, which focus primarily on using your own bodyweight as resistance to strengthen your muscles, as opposed to external weights like dumbbells or barbells. The benefit of these routines are that minimal equipment are required to perform them, and so they can be done at home if going to a gym is not something you want/can afford to do.

If you are new to exercise, The Primer routine additionally acts as a gradual physical and theoretical introduction to structured exercise programs, with a guided 14 day intro ‘build-up’ period. In this period you will go from learning 1 exercise on day 1 to a full-body training program composed of 6 exercises on day 14. Every day of the build-up there is an associated reading, to either learn how to perform one of the 6 exercises, or to learn a theoretical concept about exercise that will help you on your journey.

Neither of these programs were written specifically for people with hypermobility (because it is impossible to write a hypermobility-specific cookie cutter routine, due to how complex and varied hypermobility is), so there are some other considerations and things that you should know as a hypermobile person on your journey of getting stronger that are not written in the Primer, but I will seek to cover those things independently in my future writings about hypermobility. (Coming Soon!)

Part 2: Summary Points

- Muscles, even when they aren’t consciously contracting, exert constant tension on a joint called ‘Tone’

- The strength of a muscle impacts the amount of force produced by its ‘tone’

- Massive strength imbalances between antagonist muscles can contribute to joint instability through imbalances in the ‘tone’ tug-of-war.

- Strengthening your muscles in a proportional, balanced way is one of the best ways to reduce the incidence/severity of joint subluxation.

- The best approach for hypermobile people to get stronger is to seek out a qualified professional to guide them, but in the absence of that, it is not inherently unsafe to start exercising independently as a hypermobile person on principle, and if you do choose to start exercising, the BWF Primer is a good starting point!

Support the Creator!

If you like my content a lot and want to say thanks to the person that made it (me!), you can send me a one-off or monthly tip on Ko-fi here! Also, I have a premium exercise library hosted on this site with currently 325 exercises in it that you can subscribe to for only £5 per month. If you do decide to sign up, it’d be even better for you than donating anyway, because you get some nice premium content as well!

(ON THE PRESENCE OF ADS ON THE SITE:) I make the majority of my content for free because I simply want to help people as much as I can, and want to make fitness as accessible and easy to understand as possible, but running this site has some costs associated with it and like everyone in this world I’ve got bills to pay! I have had manual donation buttons and optional paid subscriptions on my site for years so I could avoid hosting ads for as long as possible, but the number of supporters to the site has not grown proportionally with increased traffic (and associated running costs from improvements to the site) over time.

Ultimately, that has informed the decision to host ads on the site. In an ideal world, if I were able to get enough consistent supporters to the site, then I could go back to making the site fully ad-free. At the same time I recognise that is not realistic, as a lot of people who appreciate my content the most do so because it is completely free, and would ultimately rather choose a few ads in my articles than having to pay for access.