Important Note: This guide was written way back in mid-2016 and hasn’t been updated since then, yet still gets quite a bit of traffic. I’ve learned a lot since then and no longer necessarily agree with many of the Mobility tests/standards I put forth in this guide as a standard baseline for the general population. I am planning to come back to this assessment at some point and update it to reflect my current professional opinion and practice.

However, people seem to get a lot of value out of the original even so many years later, and in its current form can still be very useful for individuals within the fields of dance, gymnastics, circus and contortion, so I will leave it up in the meantime!

If you have highlighted any areas of Mobility you want to learn how exactly to improve Mobility, sign up to my Mobility Library for £5/month and come say Hi in the Member’s Discord Server!

Mobility Assessment: Intro

Having balanced and good Mobility, whether or not you are an athlete or train regularly, is important to prevent injury and make sure you are happy, healthy and pain free. Being able to give yourself a Mobility assessment is a great way of telling what your focus areas are, so you can get to work and prevent injury!

DISCLAIMER: One important thing to note is that I am not a physical therapist or licensed physiotherapist. This assessment is not intended to a be replacement for getting proper treatment. Even if I was a physical therapist, a self assessment will never be as accurate or effective as an expert having a look at you. However, for people that can’t afford physio/osteo/any other kind of treatment, or are just curious, doing this assessment is the best way to take the first step towards learning where their imbalances lie. Excluding circumstances where there is something other than joint or muscle tightness leading to your immobility, this should give you 90% (made up figure) of what you need to know, for your average person.

How to give yourself a Mobility Assessment

In each section there will be a flexibility assessment and/or a Mobility assessment. There is a key difference and it’s good to know both. If you don’t know the difference check out this tutorial. You want to have good flexibility AND good Mobility. Too much flexibility with no Mobility leads also to increased risk of injury!

You may want to do the assessment first completely cold (not warmed up or stretched) to see what your everyday Mobility is, then once again after doing a full body stretching routine, just to compare.

In each section I will highlight potential issues and tightnesses you may have if you fail the test assessment for each articulation. Eventually, I’d like to extend this page to include links to other pages and articles that I or other people have written to address those specific issues, but that is a big task and it will probably come about at a glacial pace, due to the need to focus on other projects!

For anyone that wants to be notified when it all comes out, subscribe to my youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCL5ygTs_puiGKvyw47UCBVA

As such, what is included below is the Mobility self assessment itself and what’s probably wrong with you if you failed each test. Enjoy!

Upper Body Mobility Assessment:

Shoulder Flexion:

Shoulder flexion means your ability to raise your arm up over your head, increasing the angle between your torso and your arms (or in extreme ranges, decreasing the angle between your arms and your back)

For shoulder flexion, to test your flexibility, lie flat on the ground and raise your arms overhead. If you can get your arms to lie flat on the floor above your head without needing to arch your lower back, bend your arms or excessively flare your ribs, then you’ve got at least good overhead flexibility.

As you can see, I’ve failed the test. I have terrible shoulders from an entire childhood of not doing any sports or activity or anything and just being on my computer all the time

However, if you cannot do this, you most likely have one or more of the following problems:

- Tight Lats

- Tight Pecs

- Tight Biceps Long Head

- Tight Rotator Cuff

- Tight Triceps

- Poor Thoracic Extension

To test your Mobility, lean against a wall, and get your back completely flat against the wall, then raise your arms up to touch the wall above you. Same system, if you can touch the wall without arching, flaring ribs or bending your arms, you have good overhead Mobility.

If you’ve passed the flexibility test, but not the Mobility test, then you likely have one or more of the following problems:

- Weak, Tight, Imbalanced Rotator Cuff

- Weak Serratus Anterior

- Weak Lower Traps

Once you’ve looked at your overhead Mobility with these two tests, check out this list of tutorials you can use to improve your Mobility!

Shoulder Extension:

Shoulder extension means moving your arm down back to your body from flexion. What we are actually testing here is shoulder hyperextension, which is moving your arm behind you, but I’ve called it that because 1. No one but me cares 2. I’m hesitant to ever use the word hyperextension because of how many people say “OH BUT HYPEREXTENSION IS BAD FOR YOUR JOINTS”. Don’t worry its not inherently bad for you!

To test your shoulder extension flexibility, place your hands flat on a box behind you and crouch down. If you can get 90 degrees or more between your torso and your arms while keeping a neutral spine (no rounding) then you have very good shoulder extension flexibility. For your everyday fellow, about 45 degrees is all you really need, but for those who do BWF or Gymnastics, ~90 degrees is helpful for many positions like the german hang.

If you cannot do that, you may have one or more of the following problems:

- Tight Pecs

- Tight Biceps

- Tight Anterior Delts

To test your shoulder extension Mobility, grab a broomstick, (try both prone and supine grips) and lift it behind you, with straight arms. If you can get to 90 degrees between your arms and torso, you have atleast good shoulder extension Mobility.

However, if you do not, then you may have one or more of the following problems:

- Weak Rotator Cuff

- Weak Posterior Delts

- Weak Lats/Pecs in the End Range (Can be solved by doing more stick raises)

NOTE:

It is important to have balanced Mobility between flexion and extension. If you failed both tests, that’s bad and you should fix it. If you only failed one test, thats potentially hazardous and may be a risk factor for injury, as it means some antagonist muscles will be tighter than their counterpart, which is a bad thing.

External Rotation:

External shoulder rotation is when your shoulder (and by extension your entire arm, basically) rotates in such a way that it points away from your midline.

To test your external rotation flexibility, lie flat on the ground, arms bent at a 90 degree angle, out by your sides. If you can lie the backs of your hands flat on the floor above you while keeping your back flat on the floor, you have atleast good external rotation.

If you cannot, you probably suffer from the following problem:

- Tight Internal Rotators

- e.g. Subscapularis and Teres Major

Internal Rotation:

Internal shoulder rotation is when your shoulder (and by extension your entire arm, basically) rotates in such a way that it points towards from your midline.

To test your internal rotation flexibility, lie on your back, and then shift to one side, lying in such a way that your scapula is flat on the floor, with your arm about 70 degrees out from your body, then pivot your arm in such a way that your palm comes towards the floor. If you can get your forearm about 70 degrees to the ground from vertical (more easily to measure, if you can flex your wrist and touch the ground as shown), you have good internal rotation.

However, if you cannot do this, you probably suffer from the following problems:

- Tight external rotators

- i.e. Supraspinatus and Infraspinatus

- Tight Posterior Capsule (Less Likely)

To test your Mobility in internal rotation, place your arm behind your back. That’s step one. If you can do this without scapular winging, you are doing well. If you can bring your arm further up your back, and bring the other arm overhead, grabbing the opposite hands fingers, all without winging, you have good internal rotation Mobility.

On the right, my scapula is nice and flat on my back, but I can’t get as far. On my left, I can get further but it’s not internal rotation, is scapular tilting thats giving me that extra range. That’s wrong.

However, if you cannot do this, or if you can only do this with winged scapula, you most likely sufffer from one or more of these issues:

- Weak Teres Major

- Weak Subscapularis

- Weak Serratus Anterior

- Weak Lower Traps

NOTE:

It is important to have balanced strength, flexibility and Mobility in your internal and external rotators. If you failed both tests, you’ve got a lot of work to do, if you only failed one, you are at a higher risk for impingement and your shoulders are just less stable and more likely to get injured.

Wrist and Finger Extension:

Wrist Extension is when you are decreasing the angle between the back of your hand and the top of your forearm. Finger Extension is the opposite of curling your fingers into a fist.

To test Wrist Extension flexibility, get on your hands and knees and place your hands about shoulder width apart, palms flat on the floor, and with straight arms, lean forward, keeping the heels of your hands on the floor, until you can no longer comfortably do so. If you can easily get well past 90 degrees, you have passable wrist extension, if you can get past 100 degrees you are doing well. For Calisthenics or Gymnastics athletes, for example, however, you will be seeking much more wrist extension than this due to movements like the Planche requiring massive wrist extension

If you cannot get past 90 degrees between your hand and forearm, you just have tight wrists/forearms.

To test finger extension, put your hands together, palms touching, them bend the heels of your hands away, while keeping your fingers touching. If you can get 90 degrees between the fingers and the backs of your hands, you have good finger flexion!

Wrist and Finger Flexion:

Wrist flexion is when you reduce the angle between your palm and the bottom of your forearm (like when you have very camp hands). Finger Flexion is rolling your fingers into a fist.

To test wrist and finger flexion flexibility, get on your knees and place one hand (Back to floor) in between your knees, and lean to the side of the arm that is on the floor. Curl your fingers to your palm and hold them down with your other hand and then lean towards the midline. If you can get your arm straight vertical/perpendicular to the floor, you have good wrist and finger flexion!

If not, you’ve got a lot of very tight wrist and finger extensor muscles.

Lower Body Mobility Assessment:

Internal Hip Rotation:

Confusingly, Internal Hip Rotation is when your hip rotates towards your midline, but in most internal rotation tests your knee is bent at 90 degrees, and when your hip internally rotates, your foot will point outwards. Don’t be fooled. Look at the knee, not the foot. It’s pointing IN.

There’s not a lot of internal hip rotation in most exercises or movements, but its important to balance internal hip rotation to some degree with external hip rotation which is more common (e.g. in the squat)

The cool way of testing internal hip rotation Mobility is in a squat. lean to one side and drop the other knee towards the midline. Without allowing the heel to come off the floor, if you can touch the knee to the floor, you’ve got good internal rotation!

If you can’t do a resting squat, firstly, you’ve got problems already, but if you’d like to test your internal rotation flexibility, lie flat on your back, knees together, legs bent to 90 degrees. Let your knees fall outwards. 35 degrees from vertical is a good minimum for internal rotation in this way, 45 is a good amount of internal rotation.

If you do not meet either of these criteria, then you most likely have one or more of the following problems:

- Tight External Rotators (6 tiny muscles in ya’ booty)

- Tight Glutes (Maximus and Medius)

External Hip Rotation (and Hip Flexion)

Confusingly, External Hip Rotation is when your hip rotates away from your midline, but in most external rotation tests your knee is bent at 90 degrees, and when your hip externally rotates, your foot will point inwards towards your midline. AGAIN, don’t be fooled, look at the knee, not the foot. It’s pointing away from you!

To test your external hip rotation, sit down with your flat back against a wall, both legs straight out, then cross one leg over the other so your ankle rests on the opposite knee (like you are trying to sit really cool-like). With the ankle resting on the opposite knee, bring that knee up towards your chest slowly. If you can keep your back on the wall and get your bent leg to your chest you have great external hip rotation and hip flexion. IF you can get your bent leg about 45 degrees from your chest, your external hip rotation is okay and you are certainly not inflexible by any means, and so not at much of a risk for injury in this context, but you may want to work on it.

If you can’t do this, you may suffer from one or more of the following problems:

- Tight TFL

- Tight Piriformis

- Tight Glutes (Medius and Minimus)

Hip Abduction (+ External Hip Rotation):

Hip Abduction is when your leg moves away from your midline.

To test your Abduction flexibility, sit down on the floor and tilt your pelvis so that you are sitting on your ‘sit bones’ (These have the coolest sounding anatomical name ever; ‘Ischial Tuberosity’. How cool is that?!) and not on your tailbone.

This is because your adductors (the main opposer to abduction) attach to your ischium and pubis (basically right on your sitting bones) and so it will pull your adductors taut and stop your pelvis tilting to compensate for lack of adductor flexibility.

Place your feet, bottoms together in front of you, bring your feet towards your groin and then try to bring your knees to the floor. If you can do that, you have pretty good external hip rotation, and atleast good transverse abduction.

If you do not meet these criteria, you most likely have the following problem:

- Tight Adductors

- Tight Internal Rotators

Hip Extension:

Hip Extension is when your leg travels behind your body

To test your hip extension flexibility, we are going to do the ‘Thomas Test’. This will test not only your hip extension, but could also give you some other clues about your Mobility.

Find a bench or table (Any HARD surface, nothing squishy like a bed) and lie down with your butt half hanging off the surface. Bring one knee to your chest and hold it there. Firmly push your lower back into the surface, then let the other leg hang, relaxes, off the surface. If your knee falls below 180 degrees to your body, past the surface, without your lower back coming off the table then you have good hip extension.

This is if you have sufficiently flexible hip flexors and quads. Thigh parallel to the rest of the body, and 90 degrees of knee flexion.

If not, you most likely suffer from the following problem:

- Tight Hip Flexors (Iliopsoas)

The hanging leg should be able to relax and achieve 90 degrees of knee flexion, if not, you may suffer from the follow problem:

- Tight Quads (Specifically the Rectus Femoris)

If your leg abducts (drifts outwards) then you may suffer from one or more of the following problems:

- Weak Adductors

- Tight TFL

Pike:

The ‘Pike’ is a word for a forwand bend in gymnastics. It is straight legged hip flexion, but involves different muscles than ‘hip flexion’ would in a squat, for example, so I have not used the word hip flexion. This tests achilles tendon, gastrocnemius and hamstring flexibility primarily.

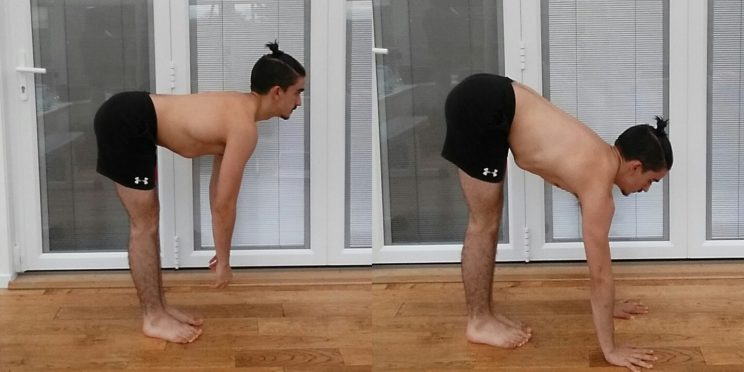

To perform the Pike flexibility test, stand with your feet together and your knees locked, and hinge your hips forward while keeping a neutral spine, by reaching to the floor 1-2 feet infront of you rather than your toes. Make sure your back stays flat the entire time. If you can get your torso flat 90 degrees from your legs, you have good pike flexibility! If you can touch your palms to the floor with a flat back, you have great pike flexibility!

If not, you may have one or more of the following problems:

- Tight Hamstrings

- Tight Calves (Gastrocnemius)

- Tight Achilles Tendon

To test your Pike Mobility, stand up and try to lift one leg, (straight legged) up in front of you, without leaning back, or bending the leg you are standing on. If you can get to 90 degrees, you have good pike Mobility!

If not, or not without bending your leg you may have one or more of the following problems:

- Weak Hip Flexors

- Weak Rectus Femoris

Squat (Ankle Dorsiflexion, Hip Flexion, Knee Flexion)

The Squat, if you don’t already know, if the position you poop in if you are hopelessly lost in the forest after dinner.

The squat is a great diagnostic tool for a lot of different things affecting your Mobility. The squat I’m talking about here is what you’ll see referred to as a ‘3rd world squat’, ‘asian squat’ or more innocuously, ‘resting squat’.

To perform this, just do a squat and lower down as far as you can, trying to keep your back flat and chest big the whole time.

If you cannot get your butt to your heels, sit up straight or have your feet pointing forwards, you may have one or more of the following problems

- Tight Calves (Soleus)

- Tight Glutes

- Tight Hamstrings

Ankle Dorsiflexion:

Ankle dorsiflexion is when the top of your foot comes closer to your shin.

To do the ankle dorsiflexion test, you do a lunge position in front of a wall stand with your testing foot and knee against a wall, standing on a ruler. Walk your testing foot out 1 inch at a time, and try to touch your knee to the wall without letting your heel come off the floor. If you can get the same 5 inches, you have good dorsiflexion! Awesome! Dorsiflexion should officially not be a limiting factor for you in achieving the resting squat, a feet forward squat, or pistol squat (or any other movement involving good dorsiflexion, apart from any extreme exceptions)

If you cannot touch your knee to the wall without your heel coming off the floor (as shown below), then move your foot an inch inwards toward the wall.

If you cannot do that, you most likely suffer from the following problems:

- Tight Soleus (Calf muscle which opposes dorsiflexion at and beyond 90 degrees of knee flexion)

- Tight Achilles Tendon

12 Comments

Leave your reply.